Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

Editor’s Notes: Pandemic!!! Plagues follow bad leadership in ancient Greek talesMarch 12, 2020 8.05am EDT Author

Associate Professor of Classical Studies, Brandeis University Disclosure statementJoel Christensen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. Partners

Brandeis University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US. In the fifth century B.C., the playwright Sophocles begins “Oedipus Tyrannos” with the title character struggling to identify the cause of a plague striking his city, Thebes. (Spoiler alert: It’s his own bad leadership.) As someone who writes about early Greek poetry, I spend a lot of time thinking about why its performance was so crucial to ancient life. One answer is that epic and tragedy helped ancient storytellers and audiences try to make sense of human suffering. From this perspective, plagues functioned as a setup for an even more crucial theme in ancient myth: a leader’s intelligence. At the beginning of the “Iliad,” for instance, the prophet Calchas – who knows the cause of a nine-day plague – is praised as someone “who knows what is, what will be and what happened before.” This language anticipates a chief criticism of Homer’s legendary King Agamemnon: He does not know “the before and the after.” The epics remind their audiences that leaders need to be able to plan for the future based on what has happened in the past. They need to understand cause and effect. What caused the plague? Could it have been prevented?

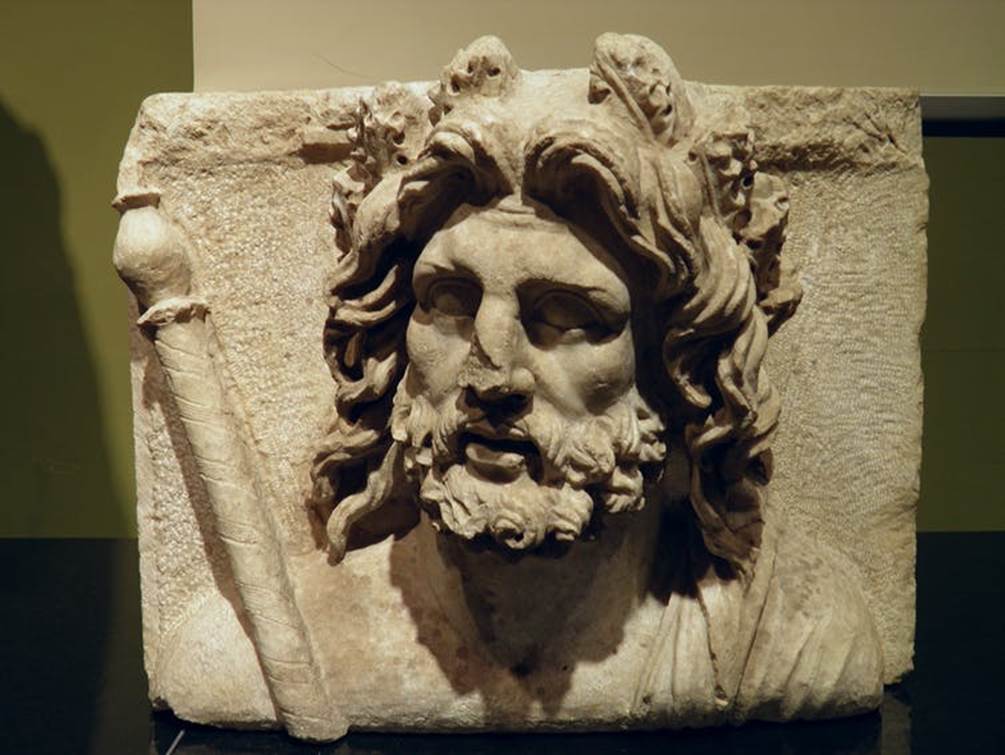

Zeus, the head Greek god, who lamented humans’ tendency to bring suffering upon themselves. Carole Raddato/Flickr, CC BY-SA People’s recklessnessMyths help their audiences understand the causes of things. As narrative theorists like Mark Turner and specialists in memory like Charles Fernyhough emphasize, people learn how to behave from stories and concepts of cause and effect in childhood. The linear sequence of before, now and after communicates the relationships between things and how we, as human beings, understand our own responsibility in the world. Plague stories provide settings where fate pushes human organization to the limit. Human leaders are almost always crucial to the causal sequence, as Zeus observes in Homer’s “Odyssey,” saying, as I’ve translated it, “Humans are always blaming the gods for their suffering / but they experience pain beyond their fate because of their own recklessness.” The problems humans create go beyond just plagues: The poet Hesiod writes that the top Greek god, Zeus, showed his disapproval for bad leaders by burdening them with military failures as well as pandemics. The consequences of human failings are a refrain in the ancient critique of leaders, with or without plagues: The “Iliad,” for instance, describes rulers who “ruin their people through recklessness.” The “Odyssey” phrases it as “bad shepherds ruin their flocks.”

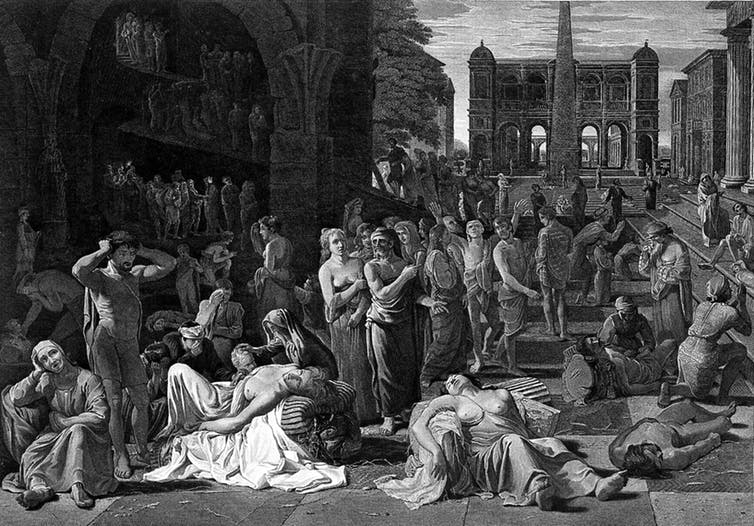

A plague in Athens. J. Fittler after M. Sweerts/Wellcome Images/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY Devastating illnessPlagues were common in the ancient world, but not all of them were blamed on leaders. Like other natural disasters, they were frequently blamed on the gods. But historians, like Polybius in the second century B.C. and Livy in the first century B.C., also frequently recount epidemics striking armies and people in swamps or cities with poor sanitation. Philosophers and physicians also searched for rational approaches – blaming the climate, or pollution. When the historian Thucydides recounts how a plague with alleged origins in Ethiopia hit Athens in 430 B.C., he vividly describes patients suffering a sudden high fever, shortness of breath and an array of sickly discharges. Those who survived the sickness had endured such delirious fevers that they might have no memory of it all. Athens as a state was unprepared to meet the challenge of that plague. Thucydides describes the futility of any human response: Appeals to the gods and the work of doctors – who died in droves – were equally useless. The disease wreaked havoc because the Athenians were massed within the city walls to wait out the Spartan armies during the Peloponnesian War. Yet despite the plague’s terrible nature, Thucydides insists that the worst part was the despair people felt from fear and the “horror of human beings dying like sheep.” Sick people died of neglect, of the lack of proper shelter and of disease spreading from improper burials in an unprepared and overcrowded city, followed by looting and lawlessness. Athens, set up as a fortress against its enemies, brought ruin upon itself.

The Spartan general Lysander orders the walls of Athens be destroyed, as part of the Athenian capitulation to Sparta. The Illustrated History of the World/Wikimedia Commons Making sense out of human flawsLeft out of plague accounts are the names of the multitudes who died in them. Homer, Sophocles and Thucydides tell us that masses died. But plagues in ancient narratives are usually the beginning, not the end of the story. A plague didn’t stop the Trojan War, prevent Oedipus’ sons from waging civil war or give the Athenians enough reasons to make peace. For years after the ravages of the plague, Athens still suffered from in-fighting, toxic politics and selfish leaders. Popular politics led to the disastrous Sicilian Expedition of 415 B.C., killing thousands of Athenians – but still Athens survived. A decade later, the Athenians again broke into civil factions and eventually prosecuted their own generals after a naval victory in 406 B.C. at Arginusae. In 404 B.C., after a siege, Sparta defeated Athens. But, as we learn from Greek myth, it was – again – really Athens’ leaders and people who defeated themselves. |