Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

Pipeline

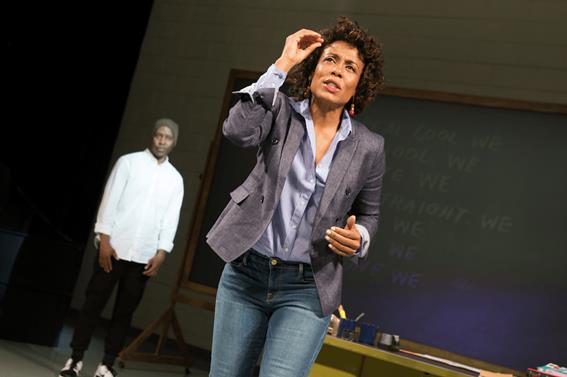

Namir Smallwood And Karen Pittman. Photos By Jeremy Daniel.

By Ron Cohen

The words come at you like machine-gun fire in Dominique Morisseau’s Pipeline, and they are piercing, powerful and well-aimed. Morisseau has in her sight two deeply complex targets: the corroding educational pipeline with its failing inner city public schools and the incredible pressures of growing up black in America.

The script centers on Nya, an African-American public high school teacher, worried to the point of panic about the future of her teen-age son, Omari. With the aid of her ex-husband’s money (he’s a successful Wall Street executive), she has sent Omari to an affluent prep school out of town, but now Omari has attacked a teacher in a classroom, hitting him and shoving him up against the blackboard. He’s being kicked out of school, is threatened with criminal charges and gone into hiding.

Omari eventually shows up in Nya’s apartment, and we learn how the attack was prompted. The class was discussing Richard Wright’s 1940 landmark novel Native Son, depicting an atmosphere of smothering racism where a young black man accidentally becomes a murderer. In asking questions about the motives of the novel’s hero, the teacher singled out Omari for responses, igniting a fit of rage.

“He ain’t just questionin’ me about Native Son,” Omari says. “He ain’t just talkin’ text. He sayin’ somethin’ else. Something beneath the question and it’s like I’m the only one who can hear it.”

As the play continues, the rage is explored more fully, in counterpoint to the chaos that happens in the school where Nya teaches, and her fears for her son’s future takes its toll on her. The suggestion of an early death for young black men, as expressed in a poem she teaches -- We Real Cool by Gwendolyn Brooks -- haunts her.

It’s a riveting narrative, which comes to a hopeful conclusion, however. Nya pleads for Omari before his school’s board, and returns to him with the beginning of trust in his own goodness. As she tells the school board, “Don’t press charges. Don’t lock away what hopes he can become. This rage is not his sin. It was never his sin.”

Under the direction of Lileana Blain-Cruz, the play has been given a high-voltage Lincoln Center Theater production. Intensity is the key note. Whether she is talking to her son, to her ex-husband or to the school security guy who may have played a role in her marriage’s breakup, Karen Pitman’s arresting performance as Nya never lets us forget she is a woman on the edge of a very foreboding precipice. Even in her quieter or few comic moments, the tension is always present and crackling. It’s a mood matched by Namir Smallwood’s deeply felt depiction of Omari and Morocco Omari’s solid portrayal of Nya’s ex-husband. (For the record: Yes, the actor has a last name that’s the same as the first name of Nya’s son.)

The intensity is further heightened with the character of Laurie, Nya’s dedicated fellow teacher, whom we meet in the teachers’ lounge. A white woman, Laurie is given to mile-a-minute, foul-mouthed arias railing against the deficiencies of the system she is trying to function under. It’s a scene-stealing turn played with ferocity by Tasha Lawrence.

Heather Velazquez And Namir Smallwood

Another fast talker is Jasmine, Omari’s school girlfriend, whose working-class parents have each taken on two jobs to send her to a private school away from the temptations and pitfalls of their neighborhood. In Heather Velazquez’s energetic embodiment, Jasmine can go on and on about her feelings and what she feels Omari is feeling with nary a breath.

The most laid-back moments come with Jaime Lincoln Smith as the school security officer. He’s a playful soul at times, even getting laughs from the he way he slurps his lunch of spaghetti from a plastic container. But he has his high-pitched moment as well, as he tries to explain the overwhelming difficulties of his job.

The production’s high-octane approach may well match much of the fervency of Morisseau’s writing, but it sometimes gives the proceedings a didactic air, especially when played against Matt Saunders’ spare set design. Small furniture vignettes are rolled on and off the stage, backed by a huge starkly white wall on which videos of hectic school scenes are sometimes projected.

It also deflects a bit from the humanity and empathy which are such a compelling part of this work. Nevertheless, so much intelligence and passion comes to the fore in Morisseau’s probing of these time-worn but still so urgent problems, it’s hard not to find yourself being caught up in them.

Off-Broadway play Playing at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater in Lincoln Center Theater 150 West 65th Street 212 239 6200 Telecharge.com Playing until August 27 |