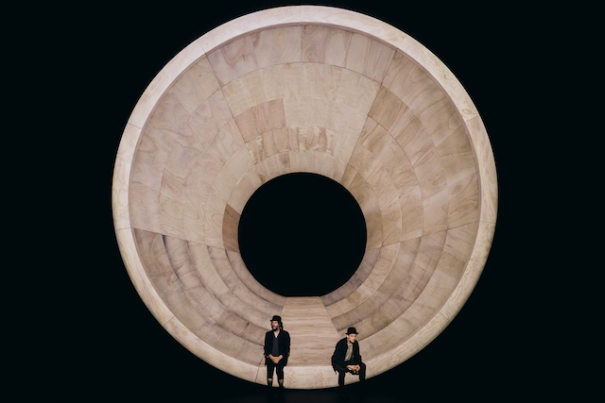

Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter (Photo: Andy Henderson)

Waiting for Godot

By Deirdre Donovan

Jamie Lloyd’s Broadway revival of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot finds Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter trading Bill and Ted’s comic banter for Beckett’s haunting silences. With Brandon J. Dirden and Michael Patrick Thornton rounding out the cast, Lloyd once again turns minimalism into a bold theatrical statement.

Before parsing the current production, it’s worth glancing back at the stage history of this play—aptly dubbed a “puzzlement” by New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson. Waiting for Godot premiered in Paris in French on January 5, 1953, at the Théâtre de Babylone, and its English-language version opened in London in 1955. The great classic has appeared on Broadway four times, each revival drawing attention for its star power and daring interpretations: the 1956 premiere with Bert Lahr and E. G. Marshall; the 2009 revival starring Nathan Lane and Bill Irwin; the 2013 staging with Sir Ian McKellen and Sir Patrick Stewart; and now the current iteration, featuring Reeves and Winter.

Lloyd’s Broadway production may well be the most chic interpretation of Beckett’s masterpiece to date. Soutra Gilmour’s monumental set design—an enormous tunnel-like structure—dispenses with Beckett’s spare stage direction, “A country road. A tree. Evening.” Instead, her sleek, modernist landscape looms over Estragon and Vladimir, making them appear small against the void and heightening the play’s sense of futility and endurance.

Beckett himself described Waiting for Godot as a reflection of the human condition rather than a story in any conventional sense. He saw it as “a play of the absurd,” dramatizing the fruitlessness of waiting for meaning in a postwar, godless world, with Vladimir and Estragon embodying humanity’s endless cycle of hope, repetition, and despair as they wait for a Godot who never comes.

Lloyd’s production captures this existential atmosphere with precision. Like the mythical Sisyphus, Vladimir and Estragon are trapped in an unending, cyclical existence that suggests both comedy and despair.

The pairing of Reeves and Winter as the two tramps—Estragon (a.k.a. Gogo) and Vladimir (a.k.a. Didi)—is a masterstroke, especially given their real-life friendship and shared past in the 1989 cult film Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. Although Reeves, making his Broadway debut, sometimes relies too heavily on gazing into the abyss while delivering Beckett’s paradoxical lines, he fares better when leaning into physical comedy, cutting the figure of a clown against Winter’s more grounded Didi. Both appear in Chaplinesque black-and-white attire (costumes by Gilmour) that underscores their everyman quality. Winter, who once played John Darling in Peter Pan on Broadway in 1979, seems more at ease onstage; his experience lends a subtle poise that anchors their exchanges.

Alex Winter, Brandon J. Dirden, Michael Patrick Thornton, Keanu Reeves (Photo: Andy Henderson)

Brandon J. Dirden (Take Me Out) as the tyrannical Pozzo and Michael Patrick Thornton (Lloyd’s A Doll’s House) as his servant Lucky are both superb. Their scenes together serve as a darker reflection of Vladimir and Estragon’s interdependence—more brutal, but equally bound by need. When Pozzo and Lucky’s power dynamic reverses in Act II (Pozzo now blind, Lucky mute), Lloyd reminds us how tenuous authority and identity can be in Beckett’s universe.

Among the production’s many highlights, Thornton’s turn as the ironically named Lucky is a genuine showstopper. His frenetic dance and torrent of nonsensical speech form a performance within a performance—a dazzling microcosm of the play itself. In this moment, Beckett’s themes of meaninglessness, the collapse of language, and the absurdity of human existence all converge with shocking clarity.

Although visually arresting, Lloyd’s ultra-chic production ultimately falls short in a few key ways. Its sleekness can smother the play’s human pulse, creating a cool distance between stage and spectator. The barren abstraction of Gilmour’s set, while conceptually striking, risks alienating the audience from the tramps’ plight. Reeves and Winter charm in moments of levity—particularly when Reeves’ Estragon quips, “Back to back like in the good old days!” and the pair mimic their Bill and Ted guitar poses—but they rarely capture the hypnotic rhythm of Beckett’s dialogue, with its circular logic and deliberate absurdity.

Alex Winter, Michael Patrick Thornton, Brandon J. Dirden, Keanu Reeves (Photo: Andy Henderson)

Still, there’s no denying the ambition and rigor of Lloyd’s vision. His Godot may not evoke the ragged humanity of Beckett’s wasteland, but it reimagines the play for a generation attuned to alienation in a sleek, postmodern key. What endures, fittingly, is the waiting itself—two figures caught between comedy and despair, suspended in the endless moment Beckett so mercilessly, and magnificently, defined.

At the Hudson Theatre, 141 W. 44th. St.

Running time: 2 hours; 15 minutes with intermission

Through January 4, 2026