Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

Looking For Leroy

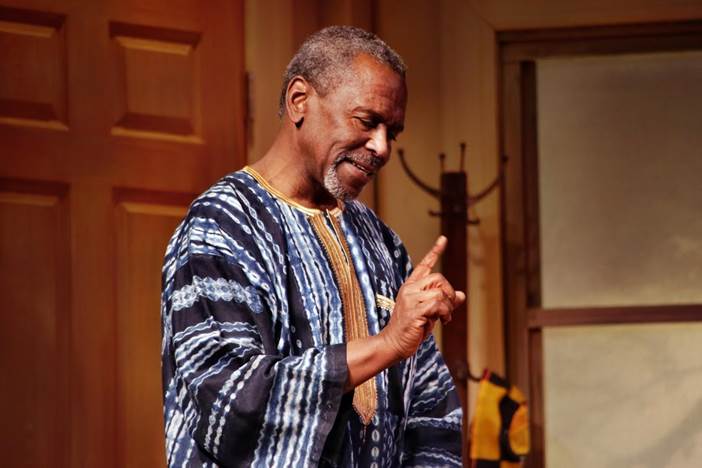

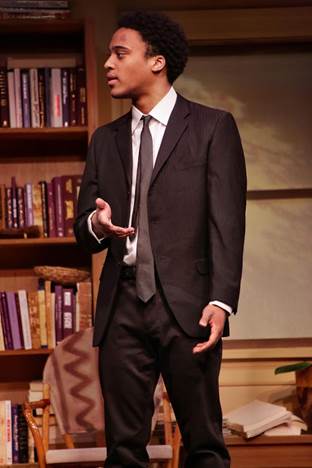

L Tyler Fauntleroy and Kim Sullivan photos by Gerry Goodstein

Looking For Leroy

R. Pikser

This two-man play by Larry Muhammed is a tribute to the late Imamu Amiri Baraka, icon of the Black theatre and Black arts movements, whose contributions still inform our consciousness. A word commonly used these days, though almost never defined, is “authenticity.” Looking for Leroy uses the life of the late Amiri Baraka to question and to try to answer what makes a man, his life, and his work, authentic.

In the course of his life, Amiri Baraka changed in many ways, both professionally and personally. He left the integrated artistic world of Greenwich Village to become a leading member of the emerging consciousness of the Black political, theatrical, and arts worlds. He embraced Afro-centrism and, for a time, excoriated all things white. He changed his name from Leroy Jones to Amiri Baraka. (Imamu is "spiritual leader" in Swahili, ultimately from the Arabic Imam). He shocked and terrified many white people and, as any great artist does, he expressed feelings that many, especially in the African American community, did not even know they had inside themselves. Later, he came to include Marxism as part of his world view. He certainly made everyone think, believing, along with W.E.B. DuBois, that the problem of America in the 20th century was the problem of the color line.

Looking for Leroy is a tribute to this man and his work. A young man, Taj, an aspiring playwright, comes to Baraka, full of awe for the master, and applies for a job as an intern. In the course of the play’s 90 minutes, as Baraka talks and talks, using Taj as a sounding board, and as Taj dares more and more to answer and even to challenge him, we are told many things, so many things that we really cannot keep track of them: There are lists of most of the important works of the Black Theatre movement; there are discussions of the Black artist and the appropriateness or even the relevance of the western canon to his art (women are barely mentioned); there are discussions of what it means to make Black theatre and who counts as, or what is, Black enough; there are discussions of the ways in which an artist, in this case Baraka, changes throughout his life and whether these changes mean he is inconsistent or that he is simply developing; there is, finally, the topic of the relationship of the old guard to the new and upcoming, who must then find their own way. In fact, Taj may be a projection of Baraka himself as, in the course of working on his play about W.E.B. DuBois, The Most Dangerous Man in America, his final work, he confronts who he was, has been, and is.

Baraka, the master, is full of himself and of pronouncements. There is little characterization or interaction of the characters as people, which has often been a criticism of Baraka’s work and is mentioned in the play. The amount of words is breathtaking and one is in awe of the performers’ memories.

Tyler Fauntleroy as Taj, the young man striving to be a Black artist, tries to find his relationship to his god as he asserts himself more and more over the course of the play. The masterful Kim Sullivan as Baraka manages to find moments of humanity, soulfulness, and even humor in between his many tirades. In fact, the most memorable moment of the play comes at the end of once scene when Baraka, exiting his study, plays air harmonica as he dances out of the room to the blues playing on the stereo.

If the play can be criticized as non-theatrical in its talkiness, the costumes, set, lighting, and sound score are all that one could wish for and more. Each of the supporting elements is a work of art. Kathy Roberson’s costuming guides us through the time frame of the play and the attitudes of the characters. When Taj comes to apply for his internship he is, sensibly, dressed in his best business attire, only to meet a dashiki-wearing Baraka who puts him down for his clothing. The next time we see Taj, he, too, is in a dashiki. After that, the passage of time is marked by a different dashiki for each scene, until the time when Baraka is wearing a shirt over his, indicating a change in his world view to encompass the importance of Marx; finally, Taj enters wearing the all-black shirt, pants, and beret that indicate that he is finding his own life.

The lighting by Antoinette Tynes never intrudes, but we see the passage of the days, the nights, and the seasons as they appear through the windows of Baraka's study, without our actually being aware of it.

Chris Cumberbatch’s set tells the audience everything they need to know, if only they can see it. We enter the theater and immediately are part of a comfortable and welcoming study with books on shelves arranged apparently for use but, upon closer examination, seen to be arranged like the composition of a painting. Other books are strewn around, obviously in the process of being consulted. African sculptures are placed at points on the walls where they do not demand our attention, but can be so easily seen that while we watch the arguments about theatre and life unfold, we come to understand that, as they frame the set, they frame Baraka’s life and work.

What is a life? What is the life of an artist? What is the life of any of us and what does it mean to be true to oneself? What is the meaning of true, and what is the self? In the case of Imamu Amiri Baraka, a large part of the answers to these questions was found in his dedication to discovering the meaning of blackness and how to cherish it and express it while living in the oppressive culture of a racist United States. Whoever he was, no one can deny that he had, and still has, a profound influence on the cultural life of this country. Now the youngsters must go and do likewise, which is his final advice to the young man who came to sit at his feet and must now go out and walk on his own. Even if Taj is Baraka himself, every time an artist creates a new work, all his past is with him and must either be discarded or must in some way come along with him.

Looking for Leroy asks us to think about the relationship between where one starts out, how one develops over time, and what it means to be true to oneself and one’s vision of the world. These are important questions for anyone, but perhaps they are more important for artists who are bridges between the world they live in and their inner vision. As Baraka’s work still resonates with us, so do these questions.

Looking for LeRoy New Federal Theatre February 28th-March 31st, 2019 Castillo Theater 543 West 42nd Street Tickets: $40; Seniors: $30 www.castillo.org; www.newfederaltheatre@aol.com 2123 353 1176 |