Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

MORNING’S AT SEVEN

MORNING’S AT SEVEN

by Marc Miller

When actors become of a Certain Age, and casting directors don’t come calling as they once did, what are they to do? Well, there’s always Morning’s at Seven. Paul Osborn’s 1939 comedy, set in 1922, lasted only 44 performances in its initial run. But it came roaring back in 1980, in a starry, much-awarded production that those of us lucky enough to have witnessed it still recall as touching, hilarious, gorgeous, and directed, by Vivian Matalon, with a depth and precision that have seldom if ever been equaled. Another starry revival in 2002 was less impressive, and so is this latest, still-starry incarnation, at the Theatre at St. Clement’s. But don’t let the slight imperfections in Dan Wackerman’s direction or a couple of performances keep you away. Morning’s at Seven is comfort food—honest, familiar, and satisfying, and it sticks to your bones.

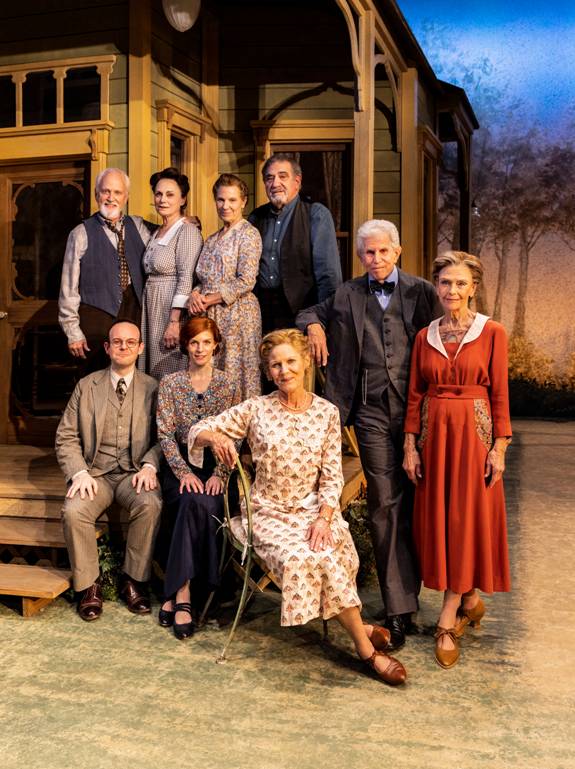

It’s the sort of play that isn’t being done much these days—conventional, mainstream, gimmick-free, and very, very white (though one wouldn’t necessarily have to cast it that way). Harry Feiner’s attractive set depicts “two backyards in a small Midwestern town,” as the script says—somewhere near Booth Tarkington territory, maybe, or William Inge on a relatively carefree day. It’s the sort of town where families tend to stick together, and that’s certainly true of the four Gibbs sisters, now approaching old age and bound by sibling supportiveness, petty jealousies, and regrets for the lives they haven’t led. Cora (Lindsay Crouse), happily married to the affable Thor (Dan Lauria), yearns to live out her remaining years free of her demanding sister Arry (Alley Mills), who has boarded with them for decades and may or may not have had a thing with Thor many years back. Next door, sister Ida (Alma Cuervo) tries to cope with the increasingly frequent mental “spells” of her husband Carl (John Rubinstein), who’s given to dazedly wandering the neighborhood and murmuring about having lost his way, meaning in life. A few blocks away, the fourth sister, smart, thoughtful Esther (Patty McCormack) spars with her supercilious spouse David (Tony Roberts), who regards the entire clan as fools. But this is no time for family conflicts, as Carl and Ida’s 40-year-old milquetoast son Homer (Jonathan Spivey) is finally introducing his longtime girlfriend Myrtle (Keri Safran) to them. Might wedding bells be in the air? Might they have to be? And if Homer finally moves out of his parents’ residence, what will that do to the tight family dynamics?

No earth-shaking issues, then, but familial conflicts presented in a straightforward, truthful, beguiling way. The small talk among the sisters, and there’s a lot of it, usually masks subtextual longings and resentments that aren’t hard to discern, while Thor’s gregariousness, Carl’s vagueness, and David’s know-it-all-ness provide useful counterpoints. And the Homer-Myrtle love story is as true and sweet as you could wish for. He’s a tongue-tied mama’s boy, she’s well-meaning and giggly and given to overpraising everyone and everything around her. We want to see these two wind up together, and there’s quite a lot of suspense about whether they will.

Arry’s the real driver of the plot, the most frustrated, least satisfied, mouthiest sister. Judith Ivey was to have played her, and wouldn’t we love to have seen that; an injury in rehearsal led to her being replaced by Mills, who, judging from a late preview, hasn’t quite figured Arry out. She’s a modern presence, rattling off Arry’s protestations in a curiously 2021 way, and while it’s fun to see her and Lauria reunited so many decades after The Wonder Years, our associations of them as Jack and Norma Arnold don’t jibe easily with the very different personas of Thor and Arry. Elizabeth Wilson, in the 1980 revival, had a hauteur, a stiffness that seemed truer to the character; her reveal of Arry’s surprising decision at play’s end brought gasps from the audience, then laughter, then a shared feeling of, Oh, well, of course that’s what she’d do. Mills’s delivery brings polite laughter, but that’s all.

It’s probably annoying to keep comparing the two productions, but Jonathan Spivey, while a well-cast, totally capable Homer, doesn’t erase the memory of a Tony-winning David Rounds. Who can forget Rounds’s horrified “Mother!” when Ida (Nancy Marchand in 1980) suggested putting a double bed in his room, to accommodate Myrtle (once they’re married, of course). On the other hand, Keri Safran is a completely delightful Myrtle, and while most of Barbara A. Bell’s costumes could represent anywhere from 1920 to 1945, the tight pink number she designed for her is a keeper—just what the nervous, desperate-to-please Myrtle would wear. There’s wonderful work, too, from John Rubinstein’s addled Carl, Alma Cuervo’s worried Ida, Lindsay Crouse’s agitated Cora, and, especially, Patty McCormack’s practical Esther: She finds humor in lines that otherwise might not have any, and when one remembers that this was the extremely skilled young actor who played Rhoda Penmark in the stage and screen versions of The Bad Seed almost 70 years ago, well, folks, this is what versatility looks like. Tony Roberts plays David close to the vest, not emoting a lot—but then, David wouldn’t, and perhaps Roberts’s calm is better suited to the material than Gary Merrill’s bombast was back in 1980. |