Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

Nat Turner in Jerusalem

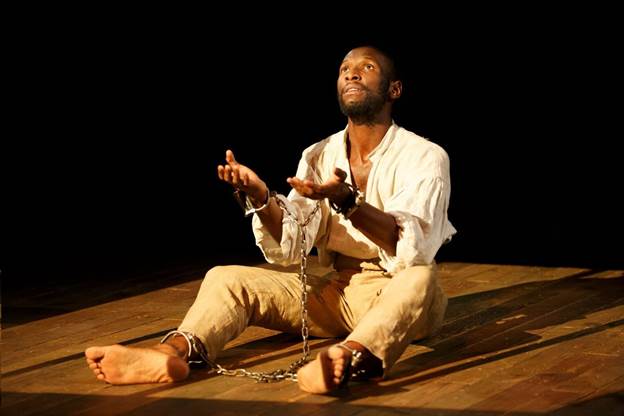

Phillip James Brannon I Joan Marcus

Nat Turner in Jerusalem

By Ron Cohen

A powerful play and a discomfiting depiction of the malaise bred by slavery on the American soul.

The hot buttons of racism get pushed with poetic fervor and chilling contemporary resonance in Nathan Alan Davis’s Nat Turner in Jerusalem.

The Jerusalem of the title is not the hallowed biblical city. Rather it is the seat of a rural county in the state of Virginia, and it is there that Nat Turner in 1831 was tried, convicted and hung as the leader of a revolt of slaves. It was an uprising that resulted in the murder of 31 adults and 24 children, including all those who had ever claimed to own Turner. In addition, a number of slaves, many of them not connected to the revolt, were killed throughout the state in the frenzy and fear ignited by it. By the time Turner himself was captured, 41 slaves and five free blacks had been tried in Jerusalem, most of them convicted and executed. (All this historical data is helpfully supplied in an insert in the play’s program.)

The Turner-led revolt is, of course, a seminal episode in U.S. history. It was the basis for the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1967 novel The Confessions of Nat Turner by William Styron, and the story is told in the forthcoming movie The Birth of a Nation, which has already won top prizes at the Sundance Film Festival.

Playwright Davis gives the tale a compact and intense theatrical currency. If the drama at times feels a bit static, the material itself and a charismatic performance by Phillip James Brannon as Turner – who sees his rebellion as a messianic mission -- keep the proceedings pulsating with arresting force. The script, through a series of six scenes, imagines Turner in his cell the night before his execution. He is visited by the somewhat smarmy lawyer Thomas R. Gray, who has been writing down Turner’s story for a confessional he will publish under his own copyright. Gray badgers Turner for details about other uprisings he may know about being planned for the future; it will make Gray’s publication only that much more valuable. In a portent for the future, Turner declares only that there will be “many uprisings.”

Rowan Vickers and Phillip James Brannon

When Gray presses Turner as to whether he feels remorse for the murders he has committed, Turner responds: “What do you think holy vengeance is supposed to look like?” As Gray cites in particular the children that were killed, Turner counters with the fates of children under slavery: “Do you not know how many children are being crushed beneath the foot of this nation? Stolen from their mothers, driven from their homes, hunted as for sport?” As for the murdered children in particular, Turner declares: “Do not grieve for your slain children. They are in heaven with their innocence. What greater danger could there be for the souls of those infants than to come of age here in Virginia?”

This conversation climaxes with one of the most intense moments in the play, when Turner makes a reference to Gray’s own daughter, and the shaken lawyer demands to know how Turner knows he has a daughter, a question never answered. However, Turner’s chains suddenly, magically, drop from his body, and the lawyer quickly exits the cell to recover. It’s a shattering depiction of the knee-jerk fear that can be engendered in racial conflict.

When Gray is not in the cell, Turner is visited by his guard, with whom he has built a tenuous sort of humane connection. Still, as the guard tells him, “It does not matter who is on the right side and who is on the wrong side. Because I would never choose your place. And I would never choose your complexion. And I would never give away my freedom. God would have to do it for me.”

It’s pungent stuff, and playwright Davis, for the most part, manages to make it seem character-driven as well as poetic. The keenly economic staging of director Megan Sandberg-Zakian also lets the language register with power, and both director and writer have a terrific accomplice in Bannon, whose portrayal of Turner is vibrantly alive, even in such problematic moments as his opening speech, in which he talks to the chain around his wrists. He creates an eminently watchable persona, who at one moment can converse with irresistible affability and who in the next moment can explode with breathtaking fury.

Bannon shares the stage with Rowan Vickers, who plays both the lawyer and the guard. Vickers gives admirable definition and credibility to both men, although some of his lawyer dialogue tends to get buried under a thick southern cracker accent.

New York Theater Workshop has given the play, developed in large part under NYTW’s auspices, exemplary production values, from Susan Zeeman Rogers spare but telling set design, Mary Louise Geiger’s moody lighting and Montana Blanco’s period-defining costumes. Nathan Leigh’s sound design is another asset, particularly in delivering the closing clangs of Turner’s cell door, although the transition music between scenes seems at times to be unnecessarily overpowering.

Most dramatically, the theater’s playing space has been reconfigured from its usual proscenium to stadium seating, with the stage situated between two sets of wooden benches on risers for the audience. (Cushions are provided.) The layout heightens the intimacy of the event, and may even suggest the seating put up for the crowds coming to watch Turner’s hanging.

Meanwhile, for a contemporary audience, Nat Turner in Jerusalem offers searing insight into how slavery has left a deep and grotesque scar that still needs healing on the American psyche.

Playing at New York Theater Workshop 79 East 4th Street 212-460-5475 Playing until October 16 |