Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

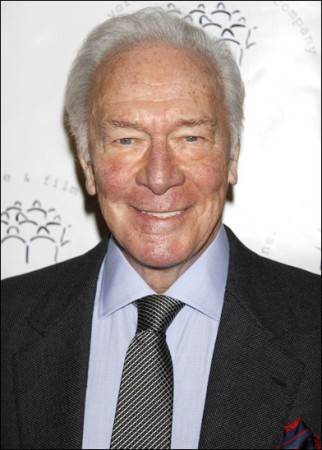

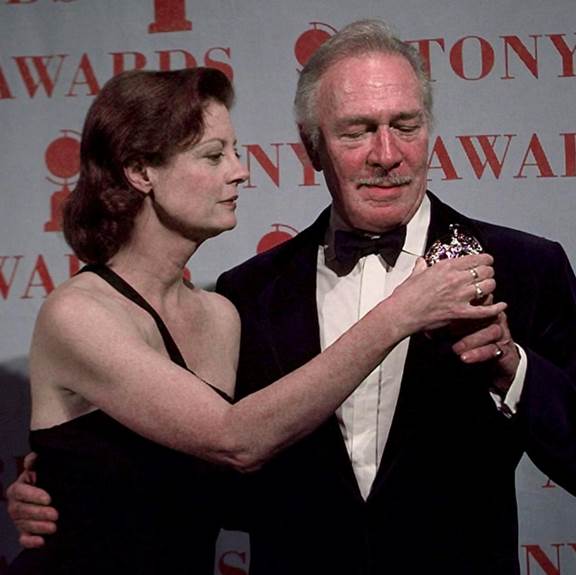

Tony and Oscar Winner Christopher Plummer, Captain Von Trapp in The Sound of Music, Dies at 91 BY ANDREW GANS FEB 05, 2021

The Canadian-born Shakespearean actor won Tony Awards for his performances in Cyrano and Barrymore. Academy Award and two-time Tony winner Christopher Plummer, most recently on Broadway in a Tony-nominated turn in the 2007 revival of Inherit the Wind, passed away February 5 at his home in Connecticut following complications from a fall. He was 91. Born December 13, 1929, in Toronto, Mr. Plummer was raised in Montreal and started acting while in high school. "My mother took me to every play that came to town, and ballet, and music," he told Playbill in 2012. An early influence was seeing Laurence Olivier in the 1944 film of Henry V. "I was still at school and went to see the film and thought...this was terrific stuff. And glamorous."

The young actor spent time learning his craft in repertory companies. "That's the way you should start," he said, "playing hundreds of different roles." Mr. Plummer later made his Broadway debut in 1954 in Diana Morgan's The Starcross Story, which also featured Eva Le Gallienne but only lasted one performance. "I thought it was the end of my career," he admitted, "but at least I'd got there. And soon afterward I was working again. I never looked back." He would go on to win two Tony Awards, for his work in a musical version of Cyrano (1974) and a tour-de-force performance in the title role of Barrymore (1997), William Luce's play based on the life of John Barrymore. (A film version, also called Barrymore and starring Plummer, premiered in 2012.) The famed actor was also Tony-nominated for his work in the aforementioned Inherit the Wind as well as King Lear (2004), No Man's Land (1994), Othello (1982), and J. B. (1959), while his other Broadway credits included Home Is the Hero, The Dark Is Light Enough, The Lark, Night of the Auk, Arturo Ui, The Royal Hunt of the Sun, The Good Doctor, and Macbeth. On the London stage, he was a member of both the Royal National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company, winning the Evening Standard Award for Best Actor in Becket; he also led Canada’s Stratford Festival under Tyrone Guthrie and Michael Langham. Although Mr. Plummer won the Academy Award and a Golden Globe for his work in Beginners, he is perhaps best remembered for his performance opposite Julie Andrews in the 1965 film version of the Rodgers and Hammerstein classic The Sound of Music, playing Captain Von Trapp. Among his numerous other film credits included Oscar-nominated turns in The Last Station (2009) and All the Money in the World (2017, replacing Kevin Spacey after initial production) plus roles in Knives Out, Danny Collins, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Tempest, Beginners, The Last Station, Caesar and Cleopatra, Man in the Chair, The New World, National Treasure, Nicholas Nickleby, A Beautiful Mind, Lucky Break, Blackheart, The Clown at Midnight, 12 Monkeys, Malcolm X, Impolite, Liar's Age, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, Souvenir, Shadow Dancing, Dreamscape, Ordeal by Innocence, The Amateur, Eyewitness, Murder by Decree, The Silent Partner, International Velvet, The Disappearance, The Assignment, The Man Who Would Be King, Conduct Unbecoming, The Return of the Pink Panther, The Royal Hunt of the Sun, Oedipus the King, Triple Cross, and The Fall of the Roman Empire.

A LIFE IN THE THEATRE: Christopher Plummer, From Stratford to The Sound of Music to Barrymore Mr. Plummer worked his magic in several solo shows, including Shakespeare with Music, created by Plummer and Michael Lankester, where he performed excerpts from four Shakespeare classics—Hamlet, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Henry V, and The Tempest—while the music of Tchaikovsky, Mendelssohn, Walton, and Lankester played; and A Word or Two. The latter, written and arranged by Plummer and directed by Tony winner Des McAnuff, offered his personal take on such literary giants as Ben Jonson, George Bernard Shaw, Shakespeare, Rudyard Kipling, A.A. Milne, Lewis Carroll, Lord Byron, Dylan Thomas, W.H. Auden, and Stephen Leacock. Mr. Plummer was the first artist to receive the Jason Robards Award, in memory of his late friend. He was also honored with the Edwin Booth Award and the Sir John Gielgud Quill Award. In 1968 he was invested as a Companion of the Order of Canada, an honorary knighthood. In 1986 he was inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame at the Gershwin Theatre, and in 2011, he was presented with the Stratford Shakespeare Festival's first Lifetime Achievement Award. (A recording of the Stratford Festival production of The Tempest, starring Plummer, was screened in movie theatres in 2014.) Mr. Plummer was 82 when he won the Oscar. He told Playbill at the time, "It kind of rejuvenates your career, makes you feel very young," adding, "I've won all sorts of awards, which I'm just as grateful for. Particularly in the theatre." Mr. Plummer is survived by third wife, Taylor, and a daughter with his first wife Tammy Grimes, Amanda Plummer. From Fast Eddy Rubin NYC

Christopher Plummer accepting an Oscar for best supporting actor at the 2012 Academy Awards. (Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

Christopher Plummer, dashing grandee of stage and film, dies at 91

By Feb. 5, 2021 at 1:27 p.m. EST

Christopher Plummer, the acclaimed stage and film star, brought both charm and an air of menace to a vast range of roles from King Lear to a Klingon villain. At 82, he added an Oscar win to a shelf of trophies that already included two Tony Awards. But Mr. Plummer will always be remembered for the one part that he professed to hate but that made him a household name: the von Trapp patriarch in “The Sound of Music.” Mr. Plummer, who was 91, died Feb. 5 at his home in Weston, Conn. The death was confirmed in a statement from his manager, Lou Pitt. The cause was not disclosed.

Since coming of age in his native Canada, Mr. Plummer saw his career propelled by his dashing matinee idol looks and his forceful characterizations of Shakespearean and other classical roles.

A major stage draw for half a century, he returned through the years to the boards of Broadway, London’s West End and the two Stratfords — England and Ontario — and shifted with ease between parts created by such disparate writers as Neil Simon and Harold Pinter.

He made a dazzling impression as Iago to James Earl Jones’s moor in “Othello” in a 1982 Broadway staging of the Shakespeare tragedy. Writing in the New York Times, theater critic Walter Kerr called Mr. Plummer’s portrayal “quite possibly the best single Shakespearean performance to have originated on this continent in our time.”

The actor conveyed the extraordinarily nimble mind of the schemer Iago with a darting physicality. “The fatigue of the man is translated into the incessant activity of the man; when the repose is impossible, one must race forward to ruin,” Kerr added. “The concept is brilliant, the execution of it perfect.” He won a Tony in the title role in a 1973 musical version of Edmond Rostand’s play “Cyrano de Bergerac.” His second Tony came in 1997 when he played his lifelong stage hero, John Barrymore, the once-great Shakespearean stage actor who drank himself to death.

Actor Christopher Plummer in 2017. (Dave Kotinsky/Getty Images)

Mr. Plummer’s dramatic gift was to imbue his performances with a measure of peril, said Antoni Cimolino, artistic director of the Stratford Festival theater in Ontario. “There is a sense of unpredictability which is the heart of theater,” he said. “And that sense of danger gave him so much power, both as a villain and also as a leading man.”

For all his stage renown — he earned seven Tony nominations — it was his casting in “The Sound of Music” that launched him to stardom. He had taken the role, he later said, because he wanted to try his hand at a musical. “I thought that was gonna be it – it’s a little film that might enjoy a certain success,” he told London’s Daily Telegraph. “And then it would go away and I would know how to sing.” The 1965 Hollywood adaptation of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical co-starred Julie Andrews as the ingenue governess of the seven warbling von Trapp children. Mr. Plummer played the brood’s stern and widowed father, a retired Austrian naval officer named Captain Georg von Trapp.

The film won five Academy Awards, including best picture, and remains one of the most popular movies ever made, a television evergreen in nearly every corner of the world. To Mr. Plummer, it was “so awful, and sentimental and gooey,” and he winced every time he recalled crooning “Edelweiss” as a single tear ran down his cheek.

His disdain for the movie — which he variously liked to call “S&M” or “The Sound of Mucus” — was widely shared by critics for its banality amid the Nazi rise. For Mr. Plummer, the film paved the way for a screen stature that would support a lavish lifestyle and a freedom to take stage roles he wanted.

In all, he appeared in more than 200 movies and TV dramas, some artistic, some wildly popular, and some eminently forgettable.

Among his more memorable performances, he was a cunning and ambitious archbishop in “The Thorn Birds” (1983), the ABC ratings smash. He was a young Rudyard Kipling in “The Man Who Would Be King” (1975) and adroitly captured the mannerisms and nuances of “60 Minutes” correspondent Mike Wallace in “The Insider” (1999), about a tobacco company whistleblower (played by Russell Crowe). In the Oscar-winning “A Beautiful Mind” (2001), he was a psychiatrist who treats the schizophrenia of future Nobel laureate John F. Nash Jr. (also played by Crowe).

In the 1991 movie “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country,” he played the Klingon general Chang, a nefarious character who enjoys spouting Shakespeare. He later had roles in films such as “Wolf” (1994), “12 Monkeys” (1995), “Syriana” (2005), “The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus” (2009) and the animated “Up” (2009). He was nominated for an Emmy for playing a supporting part as Boston’s Cardinal Bernard Law, mired in scandal, in the TV film “Our Fathers” (2005). He received an Oscar nomination for his supporting role as Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy in “The Last Station” (2009) and an Academy Award win for his supporting role in a romantic comedy, “Beginners” (2010), playing a terminally ill paterfamilias who announces he is gay.

Accepting his Oscar, the octogenarian turned to the statuette and declaimed, “Where have you been all my life?” The prize made him the oldest actor to win an Oscar, but his career was by no means over. In 2018, at the age of 88, he received another Oscar nomination for best supporting actor for his portrayal of the oil tycoon J. Paul Getty in Ridley Scott’s “All the Money in the World.” Mr. Plummer became the oldest actor ever nominated. The circumstances surrounding his role gripped Hollywood. Just six weeks before the film’s scheduled release, sexual abuse allegations against Kevin Spacey, who had originally shot the part, prompted Scott to expunge Spacey from the movie and replace him with Mr. Plummer.

Mr. Plummer told an interviewer that in “about three days I had to say yes to the script, pack, get to London and do the stuff immediately.” His performance as the tight-fisted grandfather of the kidnapped John Paul Getty III also gained him a best supporting actor nomination for the Golden Globe and Bafta awards.

“The nice part about awards and being nominated is the fact it wakes everybody up again, and makes them realize you’re alive and kicking and available,” he told the Times.

A love of literatureArthur Christopher Orme Plummer was born in Toronto on Dec. 13, 1929. An only child, he was a toddler when his parents divorced, and it would not be until his late teens that he saw his father again. Meanwhile, Mr. Plummer moved with his mother to live with his grandfather and maiden aunts in Montreal.

His mother’s family was of patrician and cultured stock — a forebear was John Abbott, a former railroad president and Canada’s first native-born prime minister. His upbringing in an atmosphere of faded grandeur proved formative to Mr. Plummer’s life and career.

“Several nights a week we would indulge in that quaint but delightful Victorian diversion — we read aloud to each other after dinner,” he wrote in his 2008 memoir, “In Spite of Myself.” The reciting helped instill in him a love of literature and language that became the hallmark of his theatrical work.

After learning the ropes and much of the stage canon in radio drama and theater repertory, he was plucked for major dramatic roles while still in his mid-20s opposite such formidable actresses as Eva Le Gallienne, Katharine Cornell and Judith Anderson.

His first appearance at Ontario’s Stratford Festival, which would become a theatrical home over his career, was as Henry V in 1956. He won praise from New York Times theater critic Brooks Atkinson, who wrote that Mr. Plummer “plays Henry magnificently not only because he has the voice, skill and range, but also because he has the grace not to exploit a heroic role.”

In his dozen later seasons at the festival, he played the title roles in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” “King Lear,” “Antony and Cleopatra” and “Macbeth.” Mr. Plummer said he grew cocky fast, turning down prestige movie work offered by the Hollywood mogul David O. Selznick in the late 1950s in favor of an offer to play Hamlet in Ontario “for 25 bucks a week. But at least it was Hamlet.” He added in his memoir that he “still harbored the old-fashioned stage actor’s snobbism toward moviemaking.”

As it happened, Mr. Plummer’s initial forays into film were less than auspicious. He debuted in director Sidney Lumet’s “Stage Struck” (1958) and that same year appeared in a drama called “Wind Across the Everglades” that quickly sank into obscurity. Six years passed before his next screen part, as the emperor Commodus in the all-star epic “The Fall of the Roman Empire.” That was quickly followed by “The Sound of Music.”

Having already rejected the allure of a studio contract for stage work, Mr. Plummer moved to England in the early 1960s to take roles in the heady, formative years of the Royal Shakespeare Company, playing Richard III, Benedick in “Much Ado About Nothing” and King Henry in Jean Anouilh’s “Becket.” His demanding career and frequent all-night carousing with Peter O’Toole, Richard Harris and other legendarily bibulous actors took a costly toll on his personal life.

“I was a lousy husband and an even worse father,” he wrote, singling out his absenteeism from his first wife, singer and actress Tammy Grimes, and their daughter, Amanda Plummer, who became a Tony-winning actress.

Mr. Plummer found the party scene of the Swinging Sixties a good fit, where he also discovered romance in the form one of the scene’s professional participants: Patricia Lewis, a showbiz columnist for a London newspaper.

One evening, sufficiently lubricated, they left their regular night spot with Lewis at the wheel. She crashed the convertible near Buckingham Palace in a smash that left Mr. Plummer unscathed but Lewis in a life-threatening coma. After her recovery, they wed in 1962 and divorced almost five years later. Mr. Plummer found the anchor for his personal life in 1968, ironically, while shooting a period sex-comedy called “Lock Up Your Daughters!”

The film bombed but one of the cast members, Elaine Taylor, would become his abiding partner, consenting to marry but only if he cleaned up his act. He agreed to give up the hard liquor and settle down. “I was just about to go down with the ship when, to the rescue came . . . a graceful angel,” he wrote in his memoir.

Survivors include his wife and daughter.

Mr. Plummer long ago abandoned his near-exclusive devotion to the stage for the richer pickings of New York and Hollywood, but he returned periodically to his acting roots to remind critics of his lacerating power in taxing roles such as Iago or Lear. In his 60s, Mr. Plummer developed a one-man show of readings from the literature that shaped his life and work. “A Word or Two” took from sources such as the Old Testament and “Winnie the Pooh,” though Shakespeare loomed large as well. A life spent mostly in the theater, he wrote, “taught me above all that there is no such thing as perfection — that in the arts there are no rules, no restrictions, no limits — only infinity.” |