Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

A Soldier’s Play

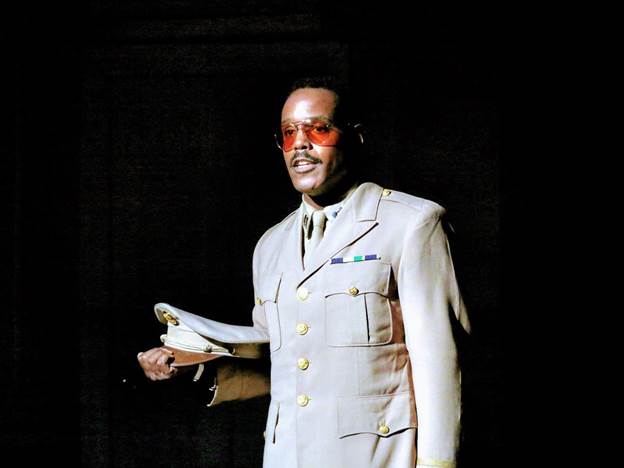

Chaz Reuben as Capt. Davenport. Photo by Jonathan Slaff.

by R. Pikser

Charles Fuller wrote A Soldier’s Play at the end of the 1960s, using the context of solving the murder of an African American (then Negro) sergeant on an army base in the south in the middle of World War II to explore the overlays and underpinnings of racism. It is an involving murder mystery, but it was, and is, much more. In the 1960s, society was vibrating with issues of race. Dr. King had recently been assassinated. Malcolm X had been assassinated a few years before that. People were in the streets. Society seemed poised for a substantive and basic change.

Unfortunately, the issues raised in A Soldier’s Play are as blazingly relevant today as they were both when the play was written and during the time period about which it was written. Some of the complex questions that Fuller raises are: What is more important - to accommodate societal prejudice in order to get a job done, or to trust that doing the job well will show the prejudice as wrong? When societal factors may well undermine important work, is it egotism to continue rather than to step aside so that the work takes precedence? Is it possible to be a racist and still do the right thing regarding those one does not like or respect? What techniques do members of oppressed groups use to survive? How do the techniques distort the members of the group? Should the techniques be condemned? Are they counter-productive? Should the people using them be condemned? What price is exacted from the soul when one tries to conform to expectations that are based on hatred? What role do class and hierarchy within and in addition to class play in oppression? How do all these questions play out in each individual? And so on.

These questions are about race and, at the same time, more than race, exploring as they do the struggle to be human in our society. The play is exhausting if one pays attention. At the same time, the audience can enjoy guessing who the culprit, or culprits, might be, rooting for one or the other of the suspects.

Charles Weldon, Artistic Director of NEC, has directed the play with much care. This production, though presented in the simple black box of the Gene Frankel Theater, has been mounted with great attention. Chris Cumberbatch’s set suggests the drabness of the barracks and the army camp grounds while allowing physical and imaginative space for flashbacks. Melody Beal’s lighting unobtrusively does its job of showing what is meant to be seen, and effacing what is not to be seen, aiding in the scene changes. But her creation of the stockade, together with the staging, chills the bones. The appearance and disappearance of the various actors as they are summoned by the officer investigating the murder, or as they perform the flashbacks that provide the dramatic tension, are seamless.

Chaz Reuben as Capt. Davenport, Buck Hinkle as Capt. Taylor. Photo by Jonathan Slaff.

Mr. Weldon has encouraged his soldiers to have fun with the group scenes, so that we fall in love with them a little bit. This affection makes the difficult parts of the play more terrible as we try to guess and to understand what happened. Gil Tucker finds not only nuance but pathos in the abrasive Sergeant Waters who hates his oppression but takes his hatred out on those below him, even as he tries to play by the rigged rules and prove his worth to those who refuse to see his abilities. Waters is not only the focal point of the play but the exemplar of what it is about. The part is juicy, and Mr. Tucker takes full advantage of it. Two other standouts are Horace Glasper and Jimmy Gary, Jr. Mr. Glasper’s Private Henson is so endearing in his awkwardness that we ache for him. Mr. Gary has made the wise choice to play his country boy, C. J. Memphis, not as the clown Sergeant Waters describes him as, but merely as gentle and sweet, bringing us back to think yet again, and more deeply, about Waters and his demons, which are ours. The only disappointing performances were those of the white officers. When a white man tells an African American to his face that he has a problems dealing with Negros as equals, or when a white man uses the word, “nigger,” there is emotion, either overt or under some sort of forced control. Institutional racism is structured into the systems of this country, but it is exemplified in the characters of actual people and it is never neutral, as we see today. One of the strengths of A Solder’s Play is how it shows the relationship of these two aspects of our national problem. Mr. Fuller’s language gives us the words, but this is a play, and the actors need to fill out the language.

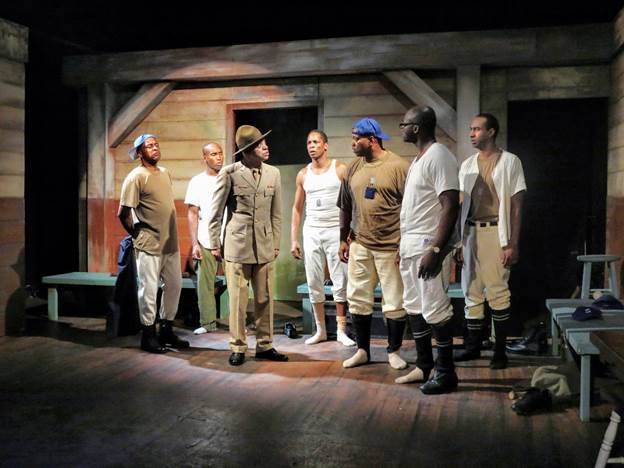

Gil Tucker, as Sgt. Waters, confronts his squad. Photo by Jonathan Slaff.

The fact that Mr. Fuller’s writing is so strong that it can well withstand less than brilliant performances, and the fact that A Soldier’s Play touches our most intimate hopes and terrors, make the play a classic in the true sense. It will endure. The Negro Ensemble Company was the training ground for many of our leading African American actors, playwrights, and technicians. This production continues the proud tradition

The Negro Ensemble Company Performances: 2/21-23 @ 7 PM, 2/24-25 @ 3 & 7, 2/28-3/1 @ 7 PM, Dark 3/2, 3/3 @ 3 & 7, closes 3/4 @ 3 PM. Gene Frankel Theater 24 Bond Street New York, NY Tickets: $35; Students, Seniors, Groups of 10 or more, $30 212 582 5860 nec.org |